U.S. expert Jeffrey Dort participated in the seminar “Challenges in Investigating Homicides of Children, Adolescents, and Young People” held on October 9. Prior to his presentation, Dort spoke with La Tercera about the challenges Chile faces in this area, as well as sharing insights from his more than 33 years of experience investigating similar cases in the United States.

Read the full interview with expert Jeffrey Dort, as provided to La Tercera.

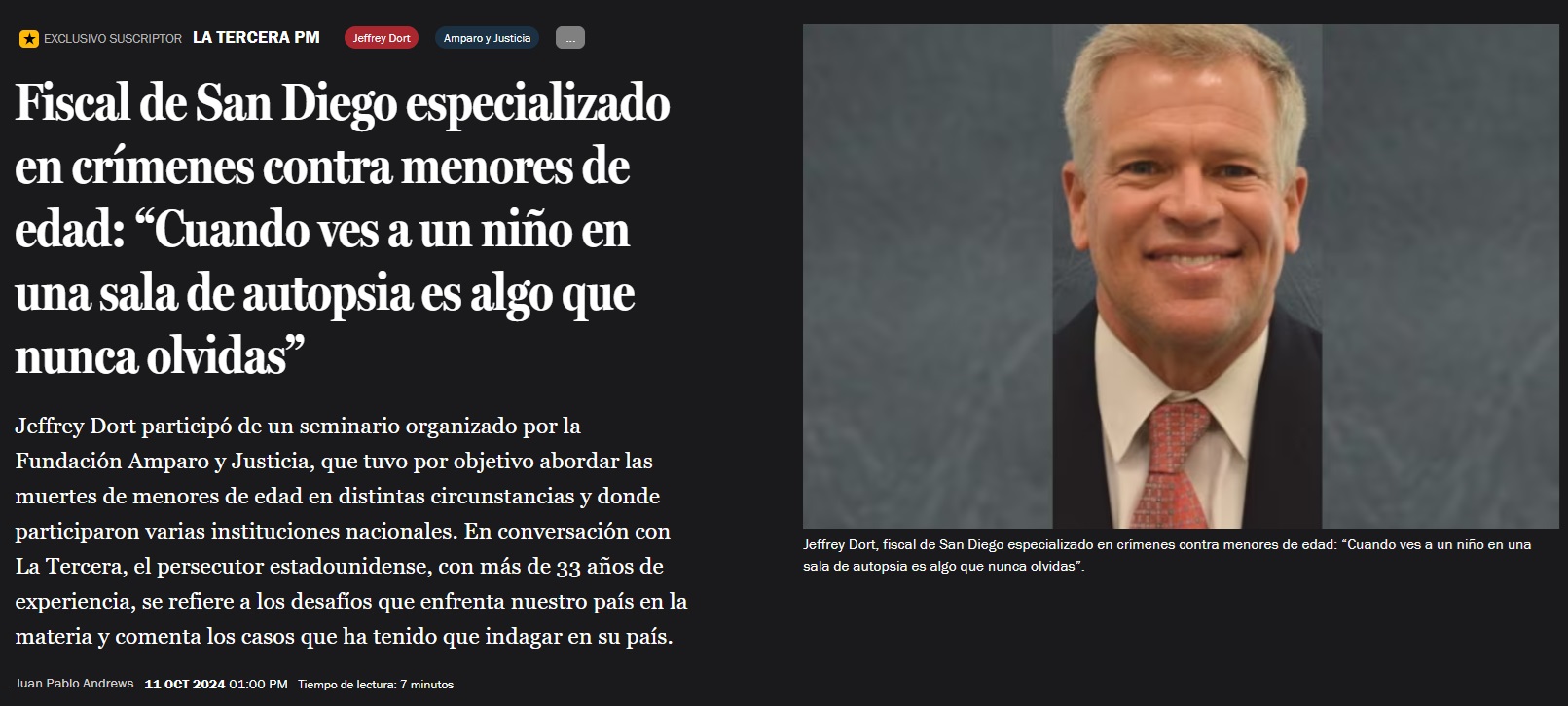

San Diego prosecutor specializing in crimes against children: “When you see a child in an autopsy room, it’s something you never forget”

Jeffrey Dort participated in a seminar organized by the Fundación Amparo y Justicia, aimed at addressing the deaths of minors under various circumstances, with the participation of several national institutions. In an interview with La Tercera, the U.S. prosecutor, with more than 33 years of experience, discusses the challenges facing Chile in this area and comments on the cases he has investigated in his country.

Despite having spent over 20 years investigating homicide cases involving minors in San Diego, California, U.S. prosecutor Jeffrey Dort says that there are moments that cannot be erased from his memory.

For instance, when he has had to see a child in an autopsy room. With over 100 cases investigated, most of which have been resolved, Dort recalls one particular case from 10 years ago that he can’t forget. It involved a three-month-old child named Juan in San Diego, who was brutally attacked by his stepfather. “That case hit me hard,” he tells La Tercera. “The man had another child and wanted his wife to spend more time with that child and not with the little baby,” he recalls. Without any apparent reason, the man, who was found guilty by U.S. courts, threw the infant against a wall, crushing his skull. “When you see a child in an autopsy room, it’s a thought you never forget. You expect older people to die or those who use weapons to die, but not children. That was very tough.”

Dort is a prosecutor in San Diego, United States, where he has specialized in pursuing homicide cases, sexual assaults, and child abuse involving minors. He is also involved in training police officers and prosecutors on investigating child homicides. He says this is crucial for achieving successful results in investigations.

On Thursday, the U.S. prosecutor participated in a seminar organized by Fundación Amparo y Justicia, where they discussed crimes involving minors, drawing on international experience and cases that have occurred in Chile. Dort was one of four international guests at the event.

The seminar included representatives from the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the Forensic Medical Service, Carabineros (police), the PDI (Investigative Police), the Judiciary, the Undersecretariat for Children, the Ministry of Health, the Subsecretariat for Crime Prevention, and the National Children’s Ombudsman. In this interview, Dort sheds light on how to lead a successful investigation when it comes to child homicide and addresses the challenges Chile faces in this area.

During the symposium, Fundación Amparo y Justicia presented a report with data obtained from the Undersecretariat of the Interior, which indicated that crimes against minors have increased by 78% in the last five years. The largest proportion of victims are adolescents between 14 and 17 years old (68%).

Recently in Chile, we’ve had cases of minors becoming involved in criminal gangs and ending up shot. How can we prevent children from joining gangs?

It’s very difficult, and it’s a problem we also have in the United States. Sometimes gangs, or older men, give children guns because the charges are much less severe if a 15-year-old is carrying a weapon than if a 25-year-old man is. It’s a process that happens in many countries, and I can’t give a response that is about laws or increasing penalties for 15-year-olds. I think it’s a systemic issue related to too many weapons, and unfortunately, violence is a way of life in large cities in big countries.

What do you see as the main problem concerning homicides in Latin America?

If you look at a map of all the homicides in Latin America, most of them are in Central America and seem to be linked to drugs. So, drug trafficking is probably the number one cause. Fortunately, regarding child crimes, in Chile the number of minors who die is much lower than in other Latin American countries. But in the research I’ve done, Chile is taking a strong approach because, in the last two or three years, the numbers have started to increase. So it seems that Chile is trying to move forward on this issue.

Dort asserts that, to address the issue of children dying in violent circumstances, the first step is “to acknowledge that it is a problem.” The second, he says, is unified work among institutions.

Domestic violence

Despite the recent surge in cases in Chile of minors killed in shootings, a recent report from the Public Prosecutor’s Office indicates that the most significant variation in this phenomenon is observed in homicides within the context of domestic violence, with a 600% increase in the past year, from 2 cases in 2022 to 14 in 2023.

What is the correct way to lead a successful investigation in a child homicide case?

That’s a difficult question because there are many different ways a child can die. And I think that’s the good thing about the seminar we held in Chile, being able to take various different examples. If a one-year-old dies, that’s very different from a five-year-old, a ten-year-old, or a fifteen-year-old. So, there’s really no single way to investigate a child homicide. I think it depends on the circumstances of the case.

But what are the main complications when investigating a child’s homicide?

For example, if a man walks into a bar and kills someone, that wouldn’t be a very difficult crime to investigate because there would be witnesses and we’d probably have the weapon. But if we have a 3-year-old child taken to the hospital and they die there, that’s a very different and very difficult case because the crime scene is probably at home. Likely, the perpetrator was one of the parents, and now you have two crime scenes: the hospital and the house. And when the police go to the house, everything has already changed. So one of the main complications with child homicides is that the crime scene is usually covered up.

So, police work is essential, right?

It’s extremely important.

Who is responsible in a case that ends without anyone being held accountable?

It’s hard to say. I don’t know about your cases, but I think when there’s a person who has gone to trial and ends up as ‘not guilty,’ everyone looks at what was not proven. Because a ‘not guilty’ doesn’t mean they didn’t do what they were accused of; it means the prosecutor and the police couldn’t prove it. I’m a prosecutor in San Diego; I’ve been one for 33 years and have had some cases with ‘not guilty’ verdicts. I know the person did it, and then I go back and look at what went wrong, why I couldn’t obtain the evidence. So, it’s multidimensional.

Lastly, regarding cases of sexual assaults against minors, what is the profile of those who commit these crimes?

It’s a person who has the ability to get close to children. A long time ago, at least in the U.S., we taught children to be concerned if a stranger was following them on the street, which is still true. But it’s not someone who gets out of a car, grabs a child, and sexually assaults them. That happens, but it’s a very rare circumstance. The profile of someone who sexually assaults a child is usually a solitary person, usually a man, usually someone from the family or who has access to the child. It could be a neighbor, but it’s usually an uncle or someone trusted by the family. It’s a crime done in secrecy, and that’s what makes it hard to uncover.